Here’s a business proposition for you: There are lots of individuals and companies out there who have a hard time accessing banking, for a variety of reasons. So why not offer the following service to the unbanked: They can give their dollars to you to store. You invest the money in bonds and generate interest, which you get to keep. In return, your customers receive shares worth $1 of the underlying asset pool. These shares are bearer assets, so your customers can use the notes like currency without any oversight on your part.

Congratulations: You’ve just built an unregistered money market fund enabling near-anonymous transfers of dollar equivalents! What could go wrong?

Crypto stablecoin issuers have built their industry around a similar model. Stablecoins act like casino chips within the crypto-conomy. To obtain tokens, you can give dollars to the issuer who then “mints” an equivalent number of stablecoin tokens on the blockchain. Those tokens can then be used to make purchases or transfer funds to others. When you want to take dollars out of the system, you can send the stablecoins back to the issuer. You get a bank transfer and the tokens are “burned” and disappear from the blockchain.

A similar model was tried before: From 2006 to 2013, a Costa Rican company called Liberty Reserve issued “digital dollars” that could be freely transferred between customers, with Liberty Reserve holding the real dollars in the interim. Liberty Reserve’s minimal KYC/AML practices landed them in hot water, and the firm was shut down by U.S. authorities. The founder, Arthur Budovsky, was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

One major difference between the current iteration of stablecoins and Mr. Budovsky’s service is that, instead of hosting all transactions internally, stablecoins are issued on public and decentralized blockchain platforms. While the stablecoin issuer initially does KYC/AML procedures when minting or burning the tokens, once the tokens are issued they have limited insight into who holds the tokens or what the tokens are being used for.

This brings us to a recent statement by the Federal Reserve board on the issuance of stablecoins on public blockchains (emphasis added):

The Board generally believes that issuing tokens on open, public, and/or decentralized networks, or similar systems is highly likely to be inconsistent with safe and sound banking practices. The Board believes such tokens raise concerns related to operational, cybersecurity, and run risks, and may also present significant illicit finance risks, because—depending on their design—such tokens could circulate continuously, quickly, pseudonymously, and indefinitely among parties unknown to the issuing bank. Importantly, the Board believes such risks are pronounced where the issuing bank does not have the capability to obtain and verify the identity of all transacting parties, including for those using unhosted wallets.

This statement was issued as part of the Fed’s new crypto rules for state banks. While these regulations will not directly apply to current stablecoin issuers, we believe that the Fed governors’ concerns about stablecoins are shared by other regulators. This statement precisely captures the risks of stablecoins as currently implemented.

Let’s take a look at one of the biggest stablecoins in crypto, the USDC token. Using a few specific examples, we will show: (1) stablecoins are regularly used by dubious actors to move massive sums of money internationally with minimal oversight, (2) stablecoins are regularly used in fraudulent transactions, and (3) stablecoin issuers provide shadow banking services for other crypto entities that are unable to access traditional banking services.

USDC is used by questionable characters to move billions of dollars internationally

Circle operates the USDC stablecoin, the second-largest stablecoin by market cap (Today $41.3 billion). USDC is widely regarded as the “stablest” stablecoin; the reserves backing the token are relatively transparent and the issuer has a strong reputation. For some reason, though, this has not translated to popularity in trading; USDC consistently lags the #1 and #3 largest stablecoins in terms of daily volume:

Circle enables some interesting characters to do some interesting things. One example is the infamous Justin Sun, who has a decidedly poor reputation even by crypto community standards. His Excellency (yes, he is also a Grenadian Ambassador) has moved over $1 billion through Circle system over the past 2 years, usually in 8- or 9-figure transactions.

Here’s one example from a couple months ago:

Justin Sun had $100 million worth of the Tether stablecoin (USDT) issued on the Tron blockchain (1). He subsequently transfers the USDT from the Tron blockchain to the Ethereum blockchain using Binance to “hop” chains (2). Next, he uses a decentralized exchange (DEX), which requires no KYC/AML to use, to swap the USDT stablecoins for an equivalent number of USDC stablecoins (3). He then sends the USDC to Circle, burning the blockchain tokens to claim real dollars (4).

In other words: Sun takes $100 million in tokens issued by an offshore and unregulated entity and converts it to real dollars in an onshore U.S. bank. It would be impossible for Circle to determine where these funds originated. Sun could have obtained the original USDT by giving Tether dollars overseas, or by using crypto as collateral to borrow the USDT. In either instance, Circle would not have any visibility into the source of the funds.

In the traditional banking world, it would likely be difficult to accomplish a $100 million transfer like this without significant oversight and monitoring. With the magic of the blockchain, it can happen in a few hours. Billions of dollars can flow without touching the traditional financial infrastructure with its pesky rules and regulations. Like the Fed pointed out:

….such tokens could circulate continuously, quickly, pseudonymously, and indefinitely among parties unknown to the issuing bank….

USDC and other stablecoins have facilitated fraud

Back in August 2022, we stumbled onto a network of fake cryptocurrency exchanges tied to a common registered agent in Colorado. We discovered that this network had pulled in tens of millions of dollars in stablecoins from victims. Briefly, the scam worked by tricking people into believing they had made large profits then hitting the marks up for “taxes” and other fees. When the victims would go to withdraw, they’d discover that the funds were missing.

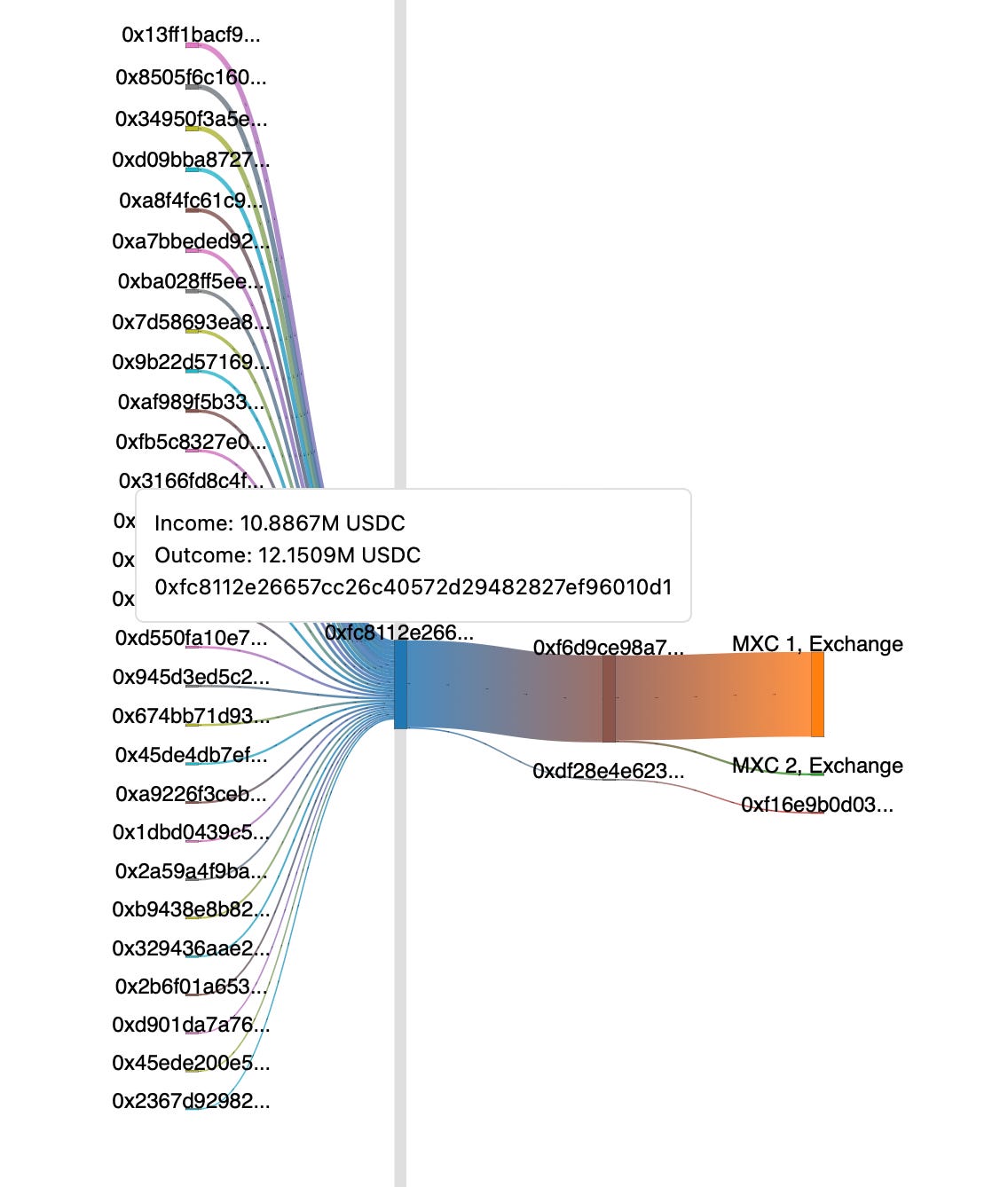

When we followed the money from a victim who alerted us to the fraud:

We discovered a network of wallets. The first layer of deposit addresses accepted transfers from a large number of individual wallets and exchanges. The deposit wallets then sent their funds forward, eventually all collecting to a core wallet. Since this wallet was created in November 2021, it has received over $60 million in USDT ($48 mil), USDC ($12 mil) and Ether ($400,000).

We made another interesting discovery when we followed where the proceeds of the fraud. All $12 million in USDC traveled to the relatively small “MEXC Global” crypto exchange. It turned out that MEXC’s U.S. operation was incorporated by the same registered agent that was involved with the fake crypto exchanges. What a strange coincidence…

All this to say: This is just one example, among many, of stablecoins like USDC being used to facilitate fraud. Due to the current design of USDC, Circle only performs KYC/AML procedures when someone directly mints or burns USDC. As a result, it is nearly impossible for Circle to proactively prevent these kinds of fraudulent activities. Again, to return to the Fed statement:

…the Board believes such risks are pronounced where the issuing bank does not have the capability to obtain and verify the identity of all transacting parties…

Circle is acting as a shadow bank for other crypto firms

Crypto exchanges have faced increasing difficulties finding banks and payment processors willing to do business with them. The list grows smaller each day as regulatory pressure increases. One example is Crypto.com, which has struggled recently to find partners willing to help it access financial markets. Their primary European payment processor, Transactive Systems, was recently shut down for flagrant money laundering violations by Lithuanian authorities.

It appears that Crypto.com found at least one work-around for this problem: According to customers, when they go to send real dollars to these exchanges the beneficiary is listed as Circle:

Based on this information, it appears that the dollars end up stashed with Circle, and the customer ends up with USDC held by Crypto.com instead. This seems reasonable based on blockchain transfers: Wallets tagged to Crypto.com have received at least $1 billion in USDC from Circle over the last year.

This means that Circle is entrusting its partners, like Crypto.com, to appropriately perform KYC/AML procedures. It also means that Circle is acting like a bank for Crypto.com and other exchange partners. Since these firms can’t access banking easily on their own, Circle warehouses their cash and issues them fungible deposit tokens in return.

Stamping out stablecoins?

While many uses for stablecoins are legitimate, in their current form these financial instruments facilitate questionable and outright illegal activities. Fraud can certainly happen on other payment services; for example, there was rampant fraud in the early days of Paypal. However, the problem with stablecoins is that their design makes appropriate oversight by the issuer nearly impossible. Once the token is transferred to an unknown third party, it can go anywhere and be used for anything.

As we were completing this article, another major stablecoin, Binance USD (BUSD), ended up in the headlines. Issued by the New York-based Paxos Trust, BUSD is the primary mechanism Binance uses to move dollars. As we have documented before, Binance has often struggled to maintain its access to banking. Binance holds billions of BUSD on its books, leaving the problem of holding real dollars to Paxos.

It turned out that the relationship between Paxos and Binance drew regulatory attention, and it was announced that the New York Department of Financial Services was investigating. Shortly thereafter, news broke that Paxos received a Wells notice from the SEC asserting BUSD is a security. And on Monday, Paxos announced that they will no longer be issuing new BUSD:

We have to wonder how long it will be before regulators take a crack at the remaining major stablecoin issuers…

Great piece

thank you for your time on this, much appreciated.